Amid the hype of data science, machine learning and AI, one important question arises within the supply chain world: Will any machine or algorithm be able to do the demand planning process by itself? Do we still need a full-blown process that requires people across different functions to interact with each other to create the best demand plan? The answer is yes. In the first of a two-part series that examines the art of science of demand planning, here we dive into the all-important art element that considers people, process and market behavior.

Why Do We Need Anything Beyond A Statistical Forecast?

While the science aspect of demand planning is very important, there are some key things that an algorithm cannot do yet. It cannot understand competitor or customer behavior, or determine the impact of external economic dynamics that could potentially affect the business. Nor is it capable of factoring in uncertainty and risk into the decision-making process.

A good forecast algorithm will eventually catch up with some of the situations described above, as customer orders or sales being used as an input to the process are affected by them. Calculations are usually rigged to put more weight on recent history as soon as a trend is detected. But there is a lag before this happens and sometimes waiting until this is noticed by a statistical model can be very costly for the business, since every month that passes compounds the issue, since the effect is cumulative. If this happens any remedial action has to be much more drastic than if smaller adjustments were made over time.

This means that the past is not always a good predictor of the future, and that human intervention is needed to overwrite the statistical forecasts and make judgement calls that avoid major remedial action down the road. The best way to execute this is through an effective alignment across functions that allows the company to stand behind a single plan that everyone believes in. This, in a nutshell, is the art component of demand planning.

Understanding the Market and your Customer

In this brave new world of rising inflation, a risk factor to consider are pricing changes. Very recently we have seen companies raising prices to balance increasing costs. Some organizations have even hired pricing gurus and developed sophisticated models for margin optimization. As part of these initiatives, it is very important to understand price elasticity, a term that economists use to describe how much more or less you will sell if the price changes.

One of the biggest mistakes when deploying these initiatives is to manage them only as standalone commercial projects that don’t all the stakeholders. Usually, the organization is very worried about margin and revenue, but doesn’t realize the impact of pricing on demand and inventory which affects productivity, working capital and customer service. Such impacts are hard to discern when looking at dollars only, since an increase in price could mask decreases in volume. It is important to understand unit changes as well.

Another impactful factor is called the bullwhip effect. It refers to how small fluctuations upstream in the supply chain become magnified as they trickle downstream. Think about how a small change in consumer behavior could create the need for higher inventory at the distribution center which in turn causes the need of a big production ramp up, which then triggers an even bigger raw material requirement. All this to have enough product in the network to support a smaller end user need. The main reason behind this situation is lack of visibility across all the supply chain, long lead times and safety stocks required at different stages in the end-to-end process.

I remember experiencing a good example of this concept in action. I was in a demand review meeting where the forecast generated by the Sales team did not make sense. They seemed very optimistic. So, when the Supply Chain team questioned the data, the Sales team made the point that the numbers provided were aligned to what the customer was selling in aggregate at their stores. But this was not consistent with the actual sales orders that the customer was placing with us. After both areas went to talk to the customer, the mystery was solved. This was an inventory reduction initiative from the client side to improve their working capital towards their fiscal year end. It turned out that both functions were right, but some information was missing. Armed with a good understanding of the situation, it was only a matter of calculating when the target inventory level would be reached by our client and then using the customer sales data as the forecast.

Additional elements that can influence your demand are promotions, movements from the competitors or new products, where an educated guess is required. Gauging this impact can be very subjective and requires a good understanding of the assumptions that are being used to determine demand. When working with retailers I have seen very simple assumptions in place that work well, for example determining how many products per store are need for a new product launch or how many more for a promotion and then just multiplying per the number of stores. Simple solutions that are easy to understand can be powerful as they rally the team behind a determined course of action.

The Art Behind Demand Planning

While Supply Chain usually does the legwork for the demand planning process, Sales is often held accountable for the forecast. Then you have input from Marketing, Product, and Operations teams that needs to be taken into consideration. There is a fine line that must be navigated where everyone needs to understand clearly what their piece of the pie is. Understanding who owns what and aligning the plan across functions is where the art of demand planning lies.

Managing this cross functional discussion is critical. A framework that I have found useful is RACI. This is used in each part of the process to describe who is responsible for each part of the work. ‘R’ is for roles, i.e., who does what part of the process. ‘A’ is for accountable, i.e., who needs to be consulted. ‘C’ is for consulted, i.e., those stakeholders whose feedback you need. ‘I’ is for informed, i.e. who needs to be informed of decisions.

This way there are no gray areas or confusion as to who is the decision maker. A suitable illustration of this can be the demand plan itself. As mentioned above, Supply Chain is usually in charge of the science portion of demand planning and getting a solid foundation in the form of a good statistical forecast. This same function facilitates the cross-functional discussion with other areas to come up with the demand plan. This could lead you to believe that Supply chain is accountable for the forecast, when they are responsible. The actual function that is accountable for the forecast is most commonly Sales. This is because they own the amount in dollars and the mix of the right product that the organization intends to commercialize.

Ironically, one of the barriers that I have encountered in the past is having leaders that want their sales team in the field focused on selling, regardless of how much or which product they sell, and not behind a computer. However, it is very critical to review at least once a month which products (and how much) are moving in the market to understand if we are going down the right path.

Gaining Consensus

There are different types of plans that exist in the business and that can be used in demand planning. The more common ones are:

- Budget or Annual Operating Plan: Done once a year with a fixed set of assumptions.

- Financial Forecast or Forecast Quarterly Update: This is an attempt to update the budget numbers to changes in the environment and is updated every three months.

- Sales and Operations Unconstrained / Constrained Demand Plan: This is updated on a monthly basis and captures the most recent circumstances, new product launches, recent historic trends and any new market intelligence. The difference between the unconstrained and constrained plan is that the former includes any operational, production, or supply constraints that impact what can be sold.

You can compare a constrained forecast to last year, last month sales, to budget or even last month’s forecast. This helps the company to understand if there is a gap versus previous commitments or substantial changes over time. But it needs to be understood clearly that the monthly constrained forecast currently discussed is taking into consideration the most recent circumstances and assumptions.

A big opportunity in this process that I have encountered over the years is when different plans exist in the company. This shifts the focus out of the most recent constrained forecast and could even create a situation where it is not being discussed cross functionally. The symptoms can be easily seen in an organization when finance has their own numbers, manufacturing is using their own forecast, sales have their own plan, while supply chain is trying to make sense of all of those and using yet another set of numbers to drive procurement. This creates real havoc and confusion and causes people to be caught like a deer in the head lights when trying to explain certain situations with their own set of data.

Sometimes having multiple plans is required by the business. If each plan is understood and used the right way, it can serve a purpose. But sometimes, it can become the easy way to avoid the tough conversations that are needed cross functionally. From my perspective, the best practice is to align into one main plan allowing executives to build contingencies based on risk levels of certain initiatives, promotions or economic variables. But Sales, Operations and Supply Chain need to have only one plan to which all metrics are applied and that aligns with the lead time needed to procure and ship each product. A good way to exemplify this is when measuring the forecast accuracy of an item with ninety days of lead time. The amount that you bought today will be based on what the forecast was three months ago.

Components of the Art of Demand Planning

- Always start the demand planning meeting with a solid foundation in the form of a good statistical forecast. Then focus on exceptional, new events or variables outside the models that could skew history, like promotions, price changes or inventory level at your customer.

- Understand who is responsible for the demand planning process and who is accountable for the actual plan. The former is the ultimate decision maker, but the areas that are responsible and consulted can provide input and pushback when required.

- Find consensus around one plan that includes the most recent circumstances and market dynamics. Having one plan that is wrong (within reason) but that rallies and aligns all the organization behind it, is better than having multiple plans across different areas.

- Allow a safe place to have the tough cross-functional conversations that are needed, discuss the data and assumptions, and learn from the iterative demand planning process.

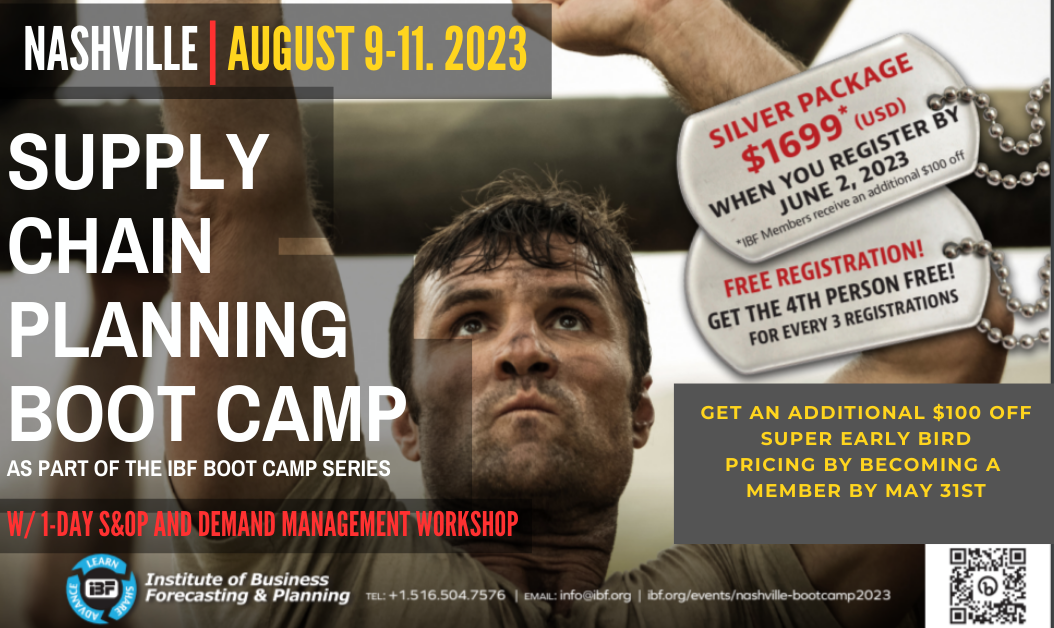

Learn the fundamentals of demand and supply planning at IBF’s Supply Chain Planning Boot Camp in Nashville, from August 9-11, 2023. You’ll learn best practices covering Materials, Resource and Work Center Planning, Inventory Planning, the Supply Review, Supply Chain Metrics and more. Includes 1-day S&OP and Demand Management workshop. Register your place.

Learn the fundamentals of demand and supply planning at IBF’s Supply Chain Planning Boot Camp in Nashville, from August 9-11, 2023. You’ll learn best practices covering Materials, Resource and Work Center Planning, Inventory Planning, the Supply Review, Supply Chain Metrics and more. Includes 1-day S&OP and Demand Management workshop. Register your place.