As consumers, we regularly face a host of product dynamics relating to the various goods we purchase, whether or not we realize it. Every year brings a plethora of new product offerings as well as old favorites touting enhanced claims: brighter, whiter, tastier, spicier — all intended to make a given product more appealing.

Marketers employ countless strategies to position their brands as more affordable, more interesting, or more likely to stand out on a shelf. Consumers may notice a familiar product available in a different size, a new flavor or fragrance, or with packaging that features distinctive new graphics or a reconfigured item count. It is also quite common to browse a shelf and discover that one of your favorite products has been discontinued. As everyday shoppers, we have come to recognize that most products are in a state of perpetual flux. As manufacturers, however, we are challenged to manage this constant change.

So, what forces drive the seemingly never-ending product innovation? Sometimes, a new product is introduced to serve a previously unmet need; a genuine “new to the world product.” Other times, market research reveals a white space in consumer tastes that may be exploited. Some companies are compelled by competitive forces to build a better mousetrap — almost a form of product Darwinism. Occasionally, the desire for variety can be a motivating factor. One needs only to consider the number of cola beverages that have cycled into and out of existence over the years to acknowledge this fact. Most of the time, however, product innovation is driven by a simple desire to increase revenue and profit. Product innovation is rarely an altruistic endeavor.

In the consumer goods sector, innovation matters — a lot. It is commonplace for new product introductions or product line extensions to account for 25% or more of a company’s top-line volume, clearly a significant portion of overall revenue. Regardless of market sector — whether chemicals, confectionaries, or beverages — innovation is the core go-to-market strategy of most companies. And although innovation is most often associated with new product introductions, innovation can and does influence sales at any point throughout the lifespan — the product life cycle — of any item.

[bar group=”content”]

From Ideation To Birth To Death: Understanding The Product Life Cycle

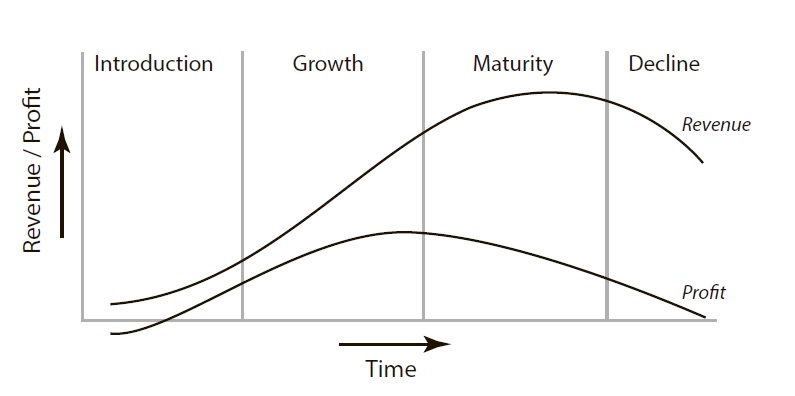

To understand product portfolio management in the context of sales and operations planning (S&OP), you first need to understand the product life cycle, the conceptual phases of revenue and profit typically observed over the lifespan of any commercial product and expressed in terms of a product life cycle curve (see Figure 1).

As you might expect, most companies have a backlog of ideas for new product introductions crowding their innovation agendas. Yet more than ever before, renovation projects are also populating these dockets. As organizations trend toward scrappier, grittier approaches to the marketplace, existing products in their mature or declining phases are reworked or renovated to satisfy new market requirements. A mature product may be changed in response to a competitive threat or to qualify for a different class of trade — by changing its size or usage count, for example.

Think of all the bulk items packed for sales in club stores, or brand-name consumer goods that are scaled down in size to serve as price-fighter SKUs (low-cost offerings designed to create barriers to entry in a price-sensitive class of trade like dollar stores).

Today’s innovation agendas are also chock-full of product renovation work including special pack outs, IRCs (instant redeemable coupons), consumer displays, new and aggressive marketing claims on packaging, compounding, or integrated packaging — all innovative product variations that are used to fight for every last dollar of top-line volume or to beat back competition. Such variants add inventory, item count, and cost to the product portfolio; but they also lend resilience to products that would likely be lost to delisting at retailers …

You can read the full version of this article, published in the Journal of Business Forecasting (2016) winter 2015-2016 edition, by filling out the form below and downloading the journal preview.